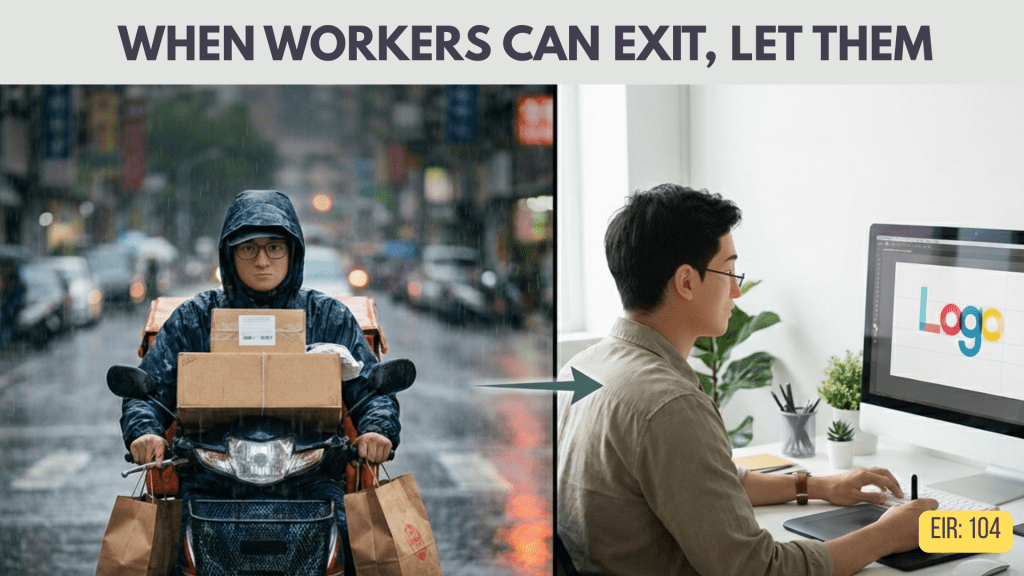

Four months ago, a friend was going through a financially tough phase. “Some money will come my way, but it’ll take months and the job market’s bad,” he told me. “So I joined a quick-commerce company as a delivery partner for immediate liquidity.”

Last month, he got a job as a graphic designer with an IT firm again.

Was this market failure needing government intervention, or market pressure working exactly as it should?

The Real Question We Should Be Asking

Workers are demanding fair pay, safety protections, and elimination of the 10-minute delivery promise. All reasonable. But are we seeing actual market failure, or just market pressure doing its uncomfortable work?

Market failure has specific criteria: monopolies eliminating choice, information gaps preventing informed decisions, harm to uninvolved third parties, or coercion preventing exit.

Gig work doesn’t meet this threshold yet.

Workers like my friend do leave when better alternatives emerge. Platforms compete for labor (watch the sign-up bonuses during worker shortages). The strike itself proves market pressure is functioning: workers collectively signaling unacceptable terms, forcing platforms to respond.

If the 10-minute delivery model is unsustainable, the market will correct it. Platforms will lose workers and be forced to change terms, or lose customers due to missed deliveries and accidents.

Why the “Exploitation” Comparison Misses the Mark

Some compare gig work to zamindari systems, colonial labor, or sweatshops. I understand the impulse. But this comparison obscures a critical distinction: coercion versus choice.

The zamindari system persisted for centuries not because it was economically optimal, but because peasants were literally bound to land. Leaving meant starvation or violence. There was no “market pressure” because there was no market, just coercion.

When workers can exit (even if alternatives are imperfect), that’s not market failure. It’s a labor market reflecting supply and demand, however uncomfortable.

The threshold question for intervention: Can workers exit?

If yes, let market pressure work. Strikes, turnover, and labor shortages will force platforms to improve or fail.

If no, then regulation is justified.

Many gig workers use these platforms as transitional income during financial difficulties. Research from the Indian Institute for Human Settlements found that 60% of gig workers in urban India view their work as temporary, using it to bridge financial gaps before moving to other opportunities. Indeed, my friend’s pattern, entering during a crisis and exiting when alternatives emerge, is what a functioning labor market looks like.

Taken too far, the exploitation angle becomes absurd. The IT industry made money off labor arbitrage for decades: paying Indian engineers less than their Western counterparts while charging clients international rates. Was that exploitation? Or was it millions of Indians using their competitive advantage (lower cost, high skill) to build careers and lift families out of poverty?

Profit is not a dirty word. It’s the incentive for entrepreneurs to risk everything and venture into uncharted terrain. Without it, platforms don’t exist, and neither do the income opportunities they create.

The Empathy Trap in Policymaking

We see gig workers toiling in rain and heat while we sit in air-conditioned comfort. This naturally triggers empathy. But empathy, however well-intentioned, is ill-suited for public policy.

Dutch historian Rutger Bregman makes this point in Humankind: A Hopeful History:

“One thing is certain: a better world doesn’t start with more empathy. If anything, empathy makes us less forgiving, because the more we identify with victims, the more we generalise about our enemies. The bright spotlight we shine on our chosen few makes us blind to the perspectives of our adversaries, because everybody else falls outside our view.”

Since we feel moved to “do something,” we reach for the most visible lever: regulation. But feeling good about policy and creating good policy are entirely different things.

Examples of empathetic policymaking gone wrong are everywhere. Take Bangladesh’s garment industry that faced pressure from the US to remove child workers.

Before garment factories, these children begged, engaged in prostitution, and did hard labor. Factories created better-paid, less arduous work. When US pressure forced factories to fire them, they didn’t go to school. They went back to prostitution and dangerous work.

Eliminating opportunities without creating alternatives can backfire.

When Good Intentions Create Bad Outcomes

Take minimum wage laws: another policy that sounds compassionate but often hurts those it aims to help. Sometimes, lower pay is the advantage a less-skilled person brings to the table. It’s their most important bargaining point in a competitive labor market. Mandating higher wages doesn’t magically make them more valuable to employers; it locks them out entirely because they can’t compete on their only competitive edge.

The worker doesn’t get “fair wages.” They get no wages.

India’s MGNREGA provides a better lesson. The rural employment guarantee scheme successfully raised agricultural wages across India by creating a fallback option. Workers gained bargaining power not through mandates on private employers, but through alternatives. Market pressure worked because workers had somewhere else to go.

Regulation that mandates benefits without considering platform sustainability risks eliminating opportunities altogether.

The Ministry of Labour’s recent draft rules illustrate the problem: 90-day minimum engagement thresholds, Universal Account Numbers through central portals, designated officers collecting contributions across hundreds of aggregators.

Two problems with the draft.

One, it’s unenforceable for a state with capacity constraints that struggles with simpler regulations. Two, it treats temporary gig work as permanent employment needing traditional protections. We’re importing first-world policies into developing-world realities. Elite imitation doesn’t just fail; it leaves things worse.

Understanding What Platforms Actually Do

The popular notion is that these platforms are merely intermediaries—brokers, or dalals in Hindi. We use the term pejoratively, implying exploitative agents who profit without adding value.

But this misunderstands what brokers actually do. The transaction costs for people on the demand and supply side to find each other are extraordinarily high. How would you, sitting at home craving biryani, find a delivery person willing to pick it up? How would that delivery person find customers without spending hours searching?

In his fascinating paper “The Economic Organisation of a P.O.W. Camp,” economist Richard A. Radford recounts how markets emerged even in the bleakest circumstances: inside a World War II prisoner-of-war camp.

Every POW received identical Red Cross parcels: biscuits, canned meat, chocolate, cigarettes. On paper, a perfect gift economy. Yet within days, trade emerged. Smokers craved more cigarettes. Non-smokers preferred chocolate. The goods themselves didn’t change. What shifted was how people valued them differently.

Soon, brokers appeared. Some acquired cigarettes from non-smokers and sold them at a premium to desperate smokers. Everyone gained from this exchange. The broker, by enabling transactions that wouldn’t otherwise occur, simply gained more.

Crucially, not a single new item was produced within the camp. Yet a robust market, complete with fluctuating exchange rates, spontaneously emerged.

Brokers, often maligned, are the lubricant of trade. They leave both buyer and seller better off, ensuring resources find their highest valued use. Platforms do this at scale, with technology, across millions of daily transactions.

The Path Forward That Actually Works

Let the strike run its course. If worker demands reflect genuine unsustainability, platforms must adapt or lose their workforce. If platforms can’t meet demands and remain viable, the business model deserves to fail. That’s creative destruction working.

Simultaneously, focus policy on expanding alternatives: skill development programs that actually lead to jobs, portable social safety nets not tied to specific employers, reducing barriers to formal employment through simpler labor laws, strengthening MGNREGA-style options that give workers bargaining power.

It’s when workers have alternatives that they gain real bargaining power. Not through mandates that may collapse opportunities or rules the state cannot enforce.

A Warning from History

People who witnessed India’s 1991 economic reforms know the end-state of socialist policies. But we’re now three decades removed, and today’s generation has no lived memory of pre-1991 India: the License Raj, the scarcity economy, the “Hindu rate of growth.”

No wonder socialism is becoming “feel-good” again. The language of worker protection, fair wages, and corporate accountability sounds righteous. But the track record is dismal.

We must let markets play their role and not let the government ruin sectors without providing genuine alternatives. The goal is creating conditions where workers have real bargaining power.

The Real Test

My friend didn’t need the government to tell him his delivery job was exploitative. He needed an alternative. And when he found one, he readily quit the gig.

The current gig worker situation represents market pressure in action. Workers are signaling unacceptable conditions through strikes and turnover. Platforms must respond or fail. That’s a functioning market doing uncomfortable but necessary work.

What’s your take? Does this strike represent market failure requiring intervention, or market pressure that should run its course?

Leave a comment