Amidst never-before scenes unfolding in SATYA, I felt a deja-vu. In fact, this Ramgopal Varma film was one of the very first movies where I became conscious of a force behind the screen.

Gangsters in films, until that point, were irredeemably evil villains or the anti-hero melodramatic types that Amitabh Bacchan embodied. Until their portrayal as people who found themselves in that path, but were as human as their neighbors in every other aspect found a stunning expression in the characters of JD and Manoj Bajpai.

For a film that showcases merciless killings, the line at the end of Satya truly moved me: “My tears for Satya are as much as for those whom he killed”.

Notwithstanding the freshness oozing out of every pore of the film, it still felt familiar.

Then, I realized. It was the story.

It was the same damn story.

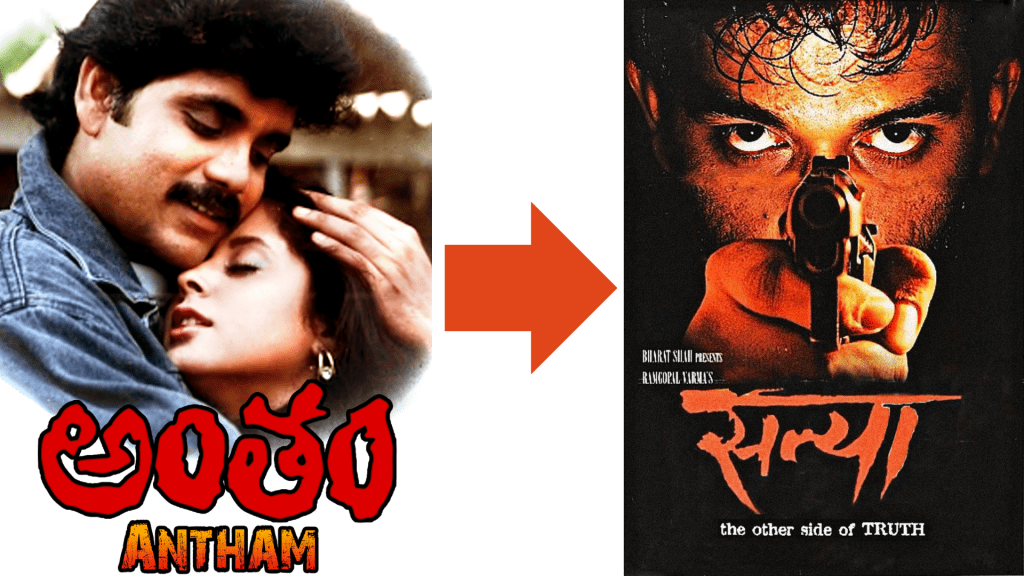

ANTHAM, made just a few years ago, had the same plot and even the same actress.

A ruthless criminal meets a girl and falls in love. So deeply in love that he even decides to renounce his profession. But, alas, it’s too late. His karma catches up with him…

In its essence, the above summary is true of both ANTHAM and SATYA.

Yet, only one of them catapulted the director to international fame.

Why is this?

If there’s one word that describes Antham, it is ‘generic’. A generic mafia don who takes the protagonist under his wing. A generic policeman who is chasing the protagonist. A generic woman whose chief attribute is, well, cuteness. Above all, a generic protagonist, whose backstory removes all mystery.

How does Satya differ?

Specificity: Set in the Mumbai mafia background.

A more pronounced causation: Bhiku Matre kills Guru Narayan. This causes Bhau to kill Matre. This causes Satya to kill Bhau. As he tries to escape, Satya gets killed too.

Bits carefully selected to reveal the characters’ character: Matre may be a don outside. At his home, he’s just a husband. Satya kills people in cold blood, yet, he’s capable of love too. Bhau may appear big-hearted, yet, he’s a politician for a reason.

Precision and escalation: Satya gets Guru Narayan killed. Precisely this act is responsible for Matre’s death. Satya gets the police commissioner killed. This leads to police encounters. This helps Bhau win elections. The victory affords Bhau the opportunity to get rid of Matre. Eventually, the commissioner’s death is avenged by his junior.

It’s as if the same raw material has now been infused with a new purpose. As if a new soul animates the entire proceedings.

When you look back, suddenly every scene is relevant. Every character pushed the plot ahead. Every element escalates.

Why Persistence Pays?

Persistence separates the successful from the average, they say. This is particularly true of writers (and artists).

But this doesn’t happen because, suddenly, the stars align in your favor.

It’s because you better-align your material so that the odds it stumbles upon success increase significantly.

From being moved by the material you go where you select the moving parts in a more clinical fashion.

You move from what swayed you to what will interest the reader.

Over time, a writer develops a taste, a discernment and intuition of what the audience may like.

Unfortunately, this only comes after years of practice.

In the beginning, most writers feel that their vision is so compelling, it can stand out on its own. As years, decades go by, they understand that the vision wasn’t so unique after all. They realize what made the greats great was the way they communicated their vision.

As they say of cinema, it’s not about the story, it’s about the storytelling.

It’s not the idea by itself that makes it grand. It’s about how the bits and pieces conspire their way towards making the idea grand.

True even for Non-fiction

“One of underestimated tasks in nonfiction writing is to impose narrative shape on an unwieldy mass of material.” — William Zinsser

In one of my editing assignments, I observed that, despite good writing, something was amiss. The ideas were good, and they were articulated well too. Yet, it lacked what I then roughly called the ‘flow’.

It was a set of disjointed paragraphs put together forcibly. One paragraph didn’t lead to the next.

I tinkered with the structure a bit. Re-organized bits. Added a few lines to make the connection obvious. Voila!

When energized by sharp editing, the writing was indisputably superior.

When I returned the draft to the writer, he remarked: “Oh, not many changes then!”.

This was both true and false.

The portions I actually rewrote were few and far between.

But the writing now had a flow that made people read up. The causation was clear. The distraction, no matter how glitzy, was all removed. And, it all made sense: from start to finish.

The writer, once he did read it all up, agreed too. This was better in a way he couldn’t recognize at first.

This was a big lesson for me. People think that a piece of writing is bad because it sucks 100%. This might be true in a few cases.

But, mostly, the writing appears poor because it hasn’t been rewritten yet. It hasn’t been structured yet. Significantly, it hasn’t been organized (or re-organized) yet.

I would venture a suggestion to you, the reader: Pick up your previous writings. Read them afresh. Chances are, you’ll find it lacking in many ways. Now, rewrite it.

Rewrite it by putting its purpose at the center. Does a line justify its existence in the new scheme of affairs? No? Edit it ruthlessly. Does one line (or one paragraph) lead to the next? Yes! Keep it on.

A good writer is not the one who writes well the first time.

A good writer is one who knows the first draft is always imperfect. And improves upon it. Improves until it’s closer to perfection than ever.

Leave a comment